Activation Functions: The Neurons' Decision Makers

Introduction

Activation functions are the heart of neural networks, introducing non-linearity into the model and enabling it to learn complex patterns. Without activation functions, a neural network would be nothing more than a linear regression model, regardless of how many layers it contains. The choice of activation function can significantly impact your model's performance, training speed, and ability to converge.

What is an Activation Function?

An activation function is a mathematical operation applied to the weighted sum of inputs at each neuron. For a given neuron, the output is calculated as:

$$ y = f(\sum_{i=1}^{n} w_i x_i + b) $$

Where:

- $x_i$ are the inputs

- $w_i$ are the weights

- $b$ is the bias

- $f$ is the activation function

Properties of an Ideal Activation Function

When designing or choosing an activation function, we look for several key properties that make it effective for training neural networks:

-

Non-linearity: The function must be non-linear to enable the network to learn complex patterns and relationships. Without non-linearity, stacking multiple layers would be equivalent to a single linear transformation, severely limiting the model's representational power.

-

Differentiability: The function should be differentiable (or at least sub-differentiable) to allow gradient-based optimization methods like gradient descent and backpropagation to work effectively. Note: ReLU is not differentiable at $x = 0$, but we typically assign a gradient of 0 or 1 at that point, which works well in practice.

-

Computational efficiency: The function should be computationally inexpensive to calculate, along with its derivative. This is crucial because activation functions are computed millions of times during training. Simple operations like thresholding (ReLU) are preferred over complex ones like exponentials (sigmoid, tanh).

-

Zero-centered: Ideally, the function should produce outputs centered around zero (mean ≈ 0). This helps with optimization by preventing systematic bias in gradient updates. Functions like tanh (-1 to 1) are zero-centered, while sigmoid (0 to 1) and ReLU (0 to ∞) are not.

-

Non-saturating: The function should avoid saturation regions where gradients become extremely small. Saturation occurs when the function flattens out for large positive or negative inputs, leading to the vanishing gradient problem. For example, sigmoid and tanh saturate at both ends, while ReLU doesn't saturate for positive values.

No single activation function perfectly satisfies all these criteria, which is why different functions are preferred for different scenarios. ReLU, for instance, trades off zero-centeredness for computational efficiency and non-saturation, making it the most popular choice for hidden layers in deep networks.

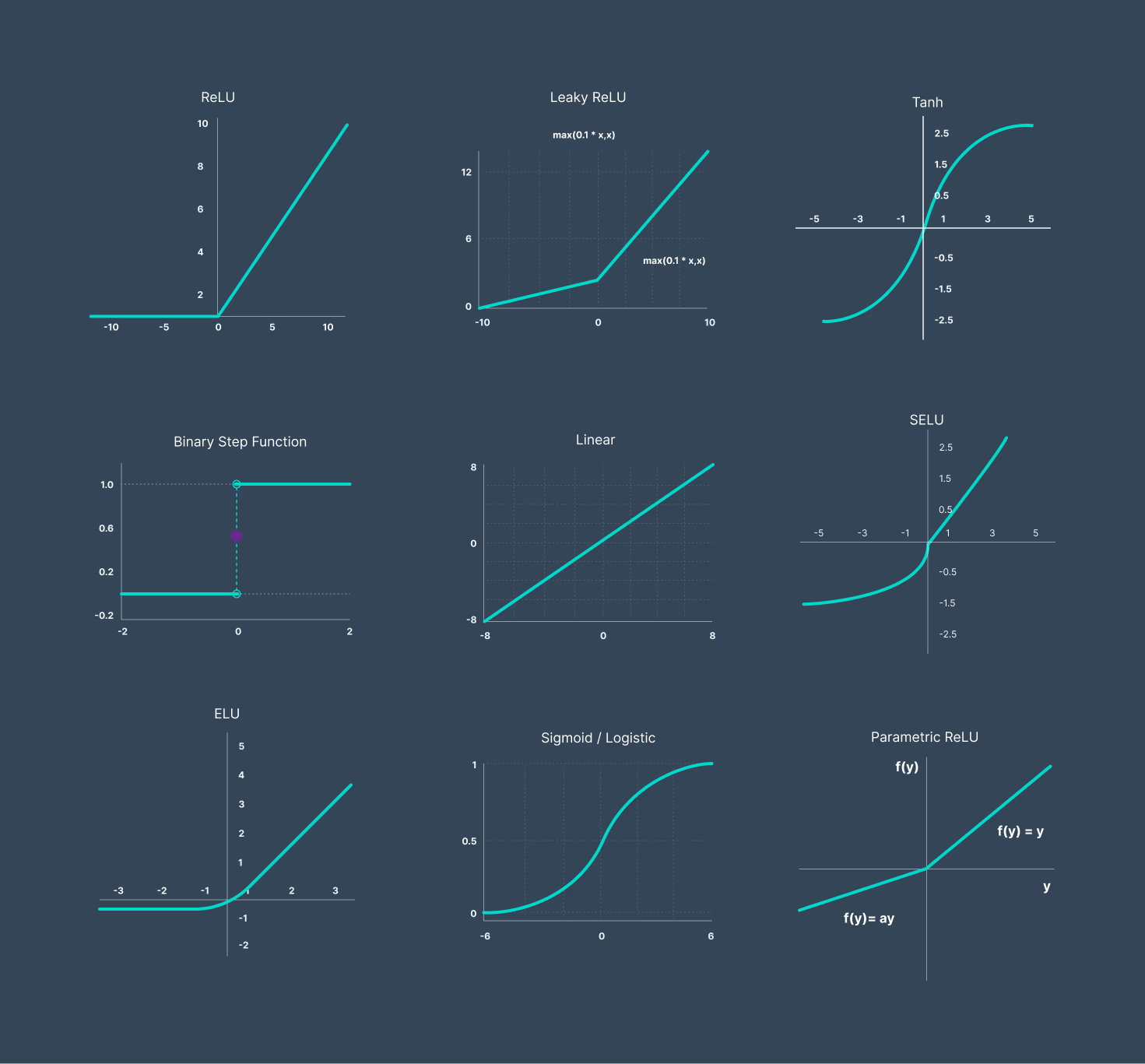

Common Activation Functions

1. Sigmoid (Logistic Function)

Mathematical Formula:

$$ \sigma(x) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-x}} $$

Derivative:

$$ \sigma'(x) = \sigma(x)(1 - \sigma(x)) $$

Range: $(0, 1)$

Advantages:

- Smooth gradient, preventing jumps in output values

- Output values bound between 0 and 1, making it excellent for probability predictions

- Clear predictions: values close to 0 or 1 indicate high confidence

- Historically significant and well-understood

Disadvantages:

- Vanishing gradient problem: Gradients become extremely small for large positive or negative values, causing training to slow down or stop

- Not zero-centered: Outputs are always positive, which can cause zig-zagging dynamics in gradient descent

- Computationally expensive due to the exponential operation

- Saturation on both ends leads to neurons "dying" during training

- Not recommended for hidden layers: Due to vanishing gradients, sigmoid should be avoided in hidden layers of deep networks. It's primarily used only in the output layer for binary classification.

Best Use Cases:

- Binary classification output layer

- When you need probability outputs (0 to 1 range)

Code Example (Binary Classification):

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

class BinaryClassifier(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, input_size, hidden_size):

super(BinaryClassifier, self).__init__()

self.fc1 = nn.Linear(input_size, hidden_size)

self.relu = nn.ReLU() # ReLU for hidden layer

self.fc2 = nn.Linear(hidden_size, 1)

self.sigmoid = nn.Sigmoid() # Sigmoid only for output layer

def forward(self, x):

x = self.fc1(x)

x = self.relu(x) # Using ReLU in hidden layer

x = self.fc2(x)

x = self.sigmoid(x) # Sigmoid in output for binary classification

return x

# Example usage

model = BinaryClassifier(input_size=10, hidden_size=64)

output = model(torch.randn(32, 10)) # batch_size=32, input_size=10

print(output.shape) # torch.Size([32, 1]) with values between 0 and 1

2. Hyperbolic Tangent (Tanh)

Mathematical Formula:

$$ \tanh(x) = \frac{e^{x} - e^{-x}}{e^{x} + e^{-x}} = \frac{2}{1 + e^{-2x}} - 1 $$

Derivative:

$$ \tanh'(x) = 1 - \tanh^2(x) $$

Range: $(-1, 1)$

Advantages:

- Zero-centered: Unlike sigmoid, outputs range from -1 to 1, making optimization easier

- Stronger gradients than sigmoid (derivatives range from 0 to 1)

- Smooth and differentiable everywhere

- Better convergence than sigmoid in practice

Disadvantages:

- Still suffers from vanishing gradient problem for extreme values

- Computationally expensive (exponential operations)

- Can saturate and kill gradients

- Not commonly used in hidden layers of deep networks

Best Use Cases:

- Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs, LSTMs)

- Hidden layers in shallow networks

- When zero-centered outputs are needed

3. Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU)

Mathematical Formula:

$$ \text{ReLU}(x) = \max(0, x) = \begin{cases} x & x > 0 \ 0 & x \leq 0 \end{cases} $$

Derivative:

$$ \text{ReLU}'(x) = \begin{cases} 1 & x > 0 \ 0 & x \leq 0 \end{cases} $$

Range: $[0, \infty)$

Advantages:

- Computationally efficient: Simple thresholding operation

- No vanishing gradient: For positive values, gradient is constant (1)

- Sparse activation: Many neurons output zero, leading to efficient representations

- Accelerates convergence of stochastic gradient descent

- Most popular activation function in deep learning

- Biological plausibility (neurons either fire or don't)

Disadvantages:

- Dying ReLU problem: Neurons can get stuck outputting zero for all inputs, effectively removing them from the network

- Not zero-centered: Outputs are always non-negative

- Unbounded output can lead to exploding activations

- Not differentiable at zero (though this is rarely a problem in practice)

Best Use Cases:

- Default choice for hidden layers in deep neural networks

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

- Most feedforward architectures

Understanding the Dying ReLU Problem

The dying ReLU problem occurs when neurons get stuck in the negative region and always output zero, effectively removing them from the network. This happens when:

- A large negative gradient flows through a ReLU neuron during backpropagation

- The weights get updated such that the weighted sum is always negative

- The neuron outputs zero for all future inputs

- Since the gradient is zero, the weights never update again - the neuron is "dead"

Practical Example:

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

# Create a simple network with ReLU

torch.manual_seed(42)

model = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(10, 5),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.Linear(5, 1)

)

# Simulate training with a large learning rate (common cause)

optimizer = torch.optim.SGD(model.parameters(), lr=1.0) # Too large!

loss_fn = nn.MSELoss()

# Training loop

for epoch in range(100):

inputs = torch.randn(32, 10)

targets = torch.randn(32, 1)

outputs = model(inputs)

loss = loss_fn(outputs, targets)

optimizer.zero_grad()

loss.backward()

optimizer.step()

# Check for dead neurons

with torch.no_grad():

test_input = torch.randn(100, 10)

activation = model[0](test_input) # Before ReLU

relu_output = model[1](activation) # After ReLU

# Count dead neurons (always output 0)

dead_neurons = (relu_output == 0).all(dim=0).sum().item()

print(f"Dead neurons: {dead_neurons} out of 5")

# Output might show: "Dead neurons: 2 out of 5"

# Check the weights of dead neurons

first_layer_weights = model[0].weight

print(f"Weight matrix shape: {first_layer_weights.shape}")

# Neurons with all negative weights for typical inputs will be dead

How to Prevent Dying ReLU:

- Use smaller learning rates

- Use proper weight initialization (He initialization)

- Consider Leaky ReLU, PReLU, or ELU

- Use batch normalization

- Monitor the percentage of dead neurons during training

Detection in Practice:

def count_dead_relu_neurons(model, data_loader):

"""Count percentage of dead ReLU neurons in a trained model"""

dead_neurons = {}

def hook_fn(name):

def hook(module, input, output):

# Check if all outputs are zero

if name not in dead_neurons:

dead_neurons[name] = (output == 0).all(dim=0)

else:

dead_neurons[name] &= (output == 0).all(dim=0)

return hook

# Register hooks on ReLU layers

hooks = []

for name, module in model.named_modules():

if isinstance(module, nn.ReLU):

hooks.append(module.register_forward_hook(hook_fn(name)))

# Run through dataset

model.eval()

with torch.no_grad():

for inputs, _ in data_loader:

_ = model(inputs)

# Remove hooks

for hook in hooks:

hook.remove()

# Report

for name, dead_mask in dead_neurons.items():

dead_count = dead_mask.sum().item()

total = dead_mask.numel()

print(f"Layer {name}: {dead_count}/{total} ({100*dead_count/total:.1f}%) dead neurons")

If you see more than 20-30% dead neurons, consider switching to Leaky ReLU or reducing your learning rate.

4. Leaky ReLU

Mathematical Formula:

$$ \text{Leaky ReLU}(x) = \begin{cases} x & x > 0 \ \alpha x & x \leq 0 \end{cases} $$

Where $\alpha$ is a small constant, typically 0.01.

Derivative:

$$ \text{Leaky ReLU}'(x) = \begin{cases} 1 & x > 0 \ \alpha & x \leq 0 \end{cases} $$

Range: $(-\infty, \infty)$

Advantages:

- Solves the dying ReLU problem by allowing small negative values

- Computationally efficient

- No saturation for positive values

- Better gradient flow than standard ReLU

- Prevents dead neurons

Disadvantages:

- Introduces an additional hyperparameter ($\alpha$)

- Performance improvements over ReLU are inconsistent

- Still not zero-centered

- Small negative slope may not be optimal for all problems

Best Use Cases:

- When you encounter dying ReLU problems

- Deep networks where gradient flow is critical

- Alternative to ReLU in CNNs

5. Exponential Linear Unit (ELU)

Mathematical Formula:

$$ f(x) = \begin{cases} x & x > 0 \ \alpha(e^x - 1) & x \leq 0 \end{cases} $$

Where $\alpha > 0$ is typically set to 1.

Derivative:

$$ f'(x) = \begin{cases} 1 & x > 0 \ f(x) + \alpha & x \leq 0 \end{cases} $$

Or equivalently:

$$ f'(x) = \begin{cases} 1 & x > 0 \ \alpha e^x & x \leq 0 \end{cases} $$

Range: $(-\alpha, \infty)$

Advantages:

- Can produce negative outputs, pushing mean activations closer to zero

- Reduces bias shift, leading to faster learning

- Smooth everywhere, unlike ReLU

- No dying ReLU problem

- More robust to noise

Disadvantages:

- Computationally expensive due to exponential operation

- Can slow down training compared to ReLU

- Introduces hyperparameter $\alpha$

- Saturation for large negative values

Best Use Cases:

- When you need mean activations closer to zero

- Networks requiring smoother gradients

- When training time is not the primary concern

6. Swish (SiLU - Sigmoid Linear Unit)

Mathematical Formula:

$$ \text{Swish}(x) = x \cdot \sigma(x) = \frac{x}{1 + e^{-x}} $$

Derivative:

$$ \text{Swish}'(x) = \text{Swish}(x) + \sigma(x)(1 - \text{Swish}(x)) $$

Range: $(-\infty, \infty)$

Advantages:

- Smooth and non-monotonic function

- Self-gated: Uses the input itself as a gate

- Shown to outperform ReLU in deep networks (discovered by Google Brain)

- Unbounded above, bounded below

- Better gradient flow than ReLU in some architectures

Disadvantages:

- Computationally more expensive than ReLU

- More complex derivative calculation

- Requires more memory during backpropagation

- Benefits may not be significant for all tasks

Best Use Cases:

- Very deep neural networks (40+ layers)

- Image classification tasks

- State-of-the-art architectures where performance matters more than speed

7. Softmax

Mathematical Formula:

$$ \text{Softmax}(x_i) = \frac{e^{x_i}}{\sum_{j=1}^{n} e^{x_j}} $$

Range: $(0, 1)$ with $\sum_{i} \text{Softmax}(x_i) = 1$

Advantages:

- Outputs a probability distribution (all outputs sum to 1)

- Differentiable

- Perfect for multi-class classification

- Amplifies differences between large values

- Interpretable as class probabilities

Disadvantages:

- Computationally expensive for large number of classes

- Can saturate and produce very small gradients

- Sensitive to outliers

- Not suitable for hidden layers

Best Use Cases:

- Output layer for multi-class classification

- Attention mechanisms in transformers

- When you need probability distributions

8. Linear (Identity) Activation

Mathematical Formula:

$$ f(x) = x $$

Derivative:

$$ f'(x) = 1 $$

Range: $(-\infty, \infty)$

Advantages:

- Simplest possible activation (no computation needed)

- Preserves the full range of values

- Constant gradient of 1 prevents gradient scaling issues

- Essential for regression tasks where you need unbounded outputs

- No saturation

Disadvantages:

- No non-linearity: Using linear activation in all layers reduces the entire network to a single linear transformation

- Cannot learn complex patterns when used throughout the network

- Only useful in the output layer for specific tasks

Best Use Cases:

- Regression problems: Predicting continuous values (house prices, temperature, stock prices)

- Output layer when you need unbounded predictions

- When the target variable can take any real value

Code Example (Regression):

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

class RegressionModel(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, input_size, hidden_size):

super(RegressionModel, self).__init__()

self.fc1 = nn.Linear(input_size, hidden_size)

self.relu = nn.ReLU() # Non-linear activation in hidden layer

self.fc2 = nn.Linear(hidden_size, hidden_size)

self.relu2 = nn.ReLU()

self.fc3 = nn.Linear(hidden_size, 1)

# No activation on output layer = Linear activation

def forward(self, x):

x = self.relu(self.fc1(x))

x = self.relu2(self.fc2(x))

x = self.fc3(x) # Linear output for regression

return x

# Example: Predicting house prices

model = RegressionModel(input_size=10, hidden_size=64)

output = model(torch.randn(32, 10)) # Can output any real value

print(output.shape) # torch.Size([32, 1])

print(output[:5]) # Values can be any real number (negative or positive)

Quick Comparison Table

Here's a comprehensive comparison of all activation functions at a glance:

| Function | Range | Zero-Centered | Saturates | Dying Neurons | Computation Cost | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sigmoid | (0, 1) | ❌ | ✅ Both ends | ❌ | High | Output: Binary classification |

| Tanh | (-1, 1) | ✅ | ✅ Both ends | ❌ | High | RNNs, LSTMs |

| ReLU | [0, ∞) | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | Very Low | Hidden layers (default) |

| Leaky ReLU | (-∞, ∞) | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | Very Low | When ReLU neurons die |

| ELU | (-α, ∞) | ~✅ | ✅ Negative | ❌ | Medium | Smoother gradients needed |

| Swish | (-∞, ∞) | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | Medium | Very deep networks (40+ layers) |

| Softmax | (0, 1) sum=1 | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ | High | Output: Multi-class |

| Linear | (-∞, ∞) | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | None | Output: Regression |

Legend:

- ✅ = Yes/Applicable

- ❌ = No/Not applicable

- ~✅ = Approximately (ELU outputs have mean closer to zero)

Activation-Loss Function Pairing

Choosing the right combination of activation and loss functions is crucial for training stability and convergence. Here's a practical guide:

📚 Want to learn more about loss functions? Check out our comprehensive guide: Loss Functions: Measuring Model Performance for detailed mathematical formulas, use cases, implementation examples, and how to handle class imbalance and custom losses.

For Classification Tasks

Binary Classification

Activation: Sigmoid (output layer)

Loss: Binary Cross-Entropy (BCELoss)

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

model_output = torch.tensor([[0.8], [0.3], [0.9]]) # After sigmoid

targets = torch.tensor([[1.0], [0.0], [1.0]])

loss_fn = nn.BCELoss()

loss = loss_fn(model_output, targets)

Alternative: No sigmoid in model + BCEWithLogitsLoss (more numerically stable)

# More stable - combines sigmoid and BCE

logits = torch.tensor([[1.5], [-0.8], [2.3]]) # Raw outputs (no sigmoid)

targets = torch.tensor([[1.0], [0.0], [1.0]])

loss_fn = nn.BCEWithLogitsLoss() # Applies sigmoid internally

loss = loss_fn(logits, targets)

Multi-class Classification

Activation: Softmax (output layer)

Loss: Cross-Entropy Loss

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

# DON'T apply softmax in your model when using CrossEntropyLoss!

logits = torch.randn(32, 10) # Raw scores for 10 classes

targets = torch.randint(0, 10, (32,)) # Class indices

loss_fn = nn.CrossEntropyLoss() # Applies softmax internally

loss = loss_fn(logits, targets)

⚠️ Important: PyTorch's CrossEntropyLoss applies softmax internally, so don't include softmax in your model's forward pass when using this loss function.

class MultiClassClassifier(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, input_size, num_classes):

super(MultiClassClassifier, self).__init__()

self.fc1 = nn.Linear(input_size, 128)

self.relu = nn.ReLU()

self.fc2 = nn.Linear(128, num_classes)

# NO softmax here when using CrossEntropyLoss!

def forward(self, x):

x = self.relu(self.fc1(x))

x = self.fc2(x) # Return raw logits

return x

For Regression Tasks

Activation: Linear/None (output layer)

Loss: Mean Squared Error (MSE) or Mean Absolute Error (MAE)

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

predictions = torch.tensor([[2.5], [1.8], [3.2]])

targets = torch.tensor([[2.3], [1.9], [3.0]])

mse_loss = nn.MSELoss()

loss = mse_loss(predictions, targets)

# Or for MAE (more robust to outliers)

mae_loss = nn.L1Loss()

loss = mae_loss(predictions, targets)

Pairing Summary Table

| Task | Output Activation | Loss Function | PyTorch |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binary Classification | Sigmoid | Binary Cross-Entropy | nn.BCELoss() |

| Binary Classification | None (preferred) | BCE with Logits | nn.BCEWithLogitsLoss() |

| Multi-class Classification | None | Cross-Entropy | nn.CrossEntropyLoss() |

| Multi-class (manual) | Softmax | Negative Log-Likelihood | nn.NLLLoss() |

| Regression | Linear/None | Mean Squared Error | nn.MSELoss() |

| Regression (robust) | Linear/None | Mean Absolute Error | nn.L1Loss() |

| Regression (combined) | Linear/None | Smooth L1 Loss | nn.SmoothL1Loss() |

Golden Rule: When the loss function applies activation internally (like CrossEntropyLoss and BCEWithLogitsLoss), don't apply that activation in your model. This improves numerical stability and prevents gradient issues.

Choosing the Right Activation Function

Here's a practical guide for selecting activation functions:

For Hidden Layers:

- Start with ReLU: It's fast, effective, and works well in most cases

- Try Leaky ReLU or ELU: If you notice dying neurons

- Use Swish: For very deep networks or when squeezing out extra performance

- Use Tanh: For RNNs and LSTMs

For Output Layers:

- Sigmoid: Binary classification (2 classes)

- Softmax: Multi-class classification (>2 classes)

- Linear (no activation): Regression problems

- Tanh: When outputs should be in range [-1, 1]

General Tips:

- Deep networks: ReLU, Leaky ReLU, or Swish

- Shallow networks: Sigmoid or Tanh can work

- CNNs: ReLU or Leaky ReLU

- RNNs/LSTMs: Tanh and Sigmoid

- Regression: Linear (identity) for output layer

Conclusion

Activation functions are fundamental building blocks of neural networks, and choosing the right one can significantly impact your model's performance. While ReLU remains the default choice for most applications, understanding the strengths and weaknesses of each activation function allows you to make informed decisions based on your specific use case.

Start with ReLU for hidden layers and appropriate output activations (Sigmoid for binary, Softmax for multi-class), then experiment with alternatives if you encounter specific problems like vanishing gradients or dying neurons. Remember that the best activation function often depends on your specific architecture, dataset, and computational constraints.